Bassano B., Durio P., Gallo Orsi U., Macchi E

eds., 1992. Proceedings of the 1st Int. Symp. on

Alpine Marmot and genera Marmota. Torino.

Edition électronique, Ramousse R., International Marmot Network, Lyon 2002

PARASITIC FAUNA OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT OF Marmota marmota IN THE WESTERN ALPS.

Bassano B.*, Sabatier B.**, Rossi L.*, Macchi E.*

* Depart. Produzioni Animali, Epidemiologia ed Ecologia, University of Torino, Via Nizza 52, 10126 Torino (I)

** Veterinarian, 322 Rue Chaudun, St. Jean Maurienne (F)

Abstract - Qualitative analysis of 181 faecal samples, quantitative analysis of other 154 from four study areas at different altitude and the necropsy of 46 Alpine marmots (Marmota marmota) were carried out with the double aim of realizing an inventory of the parasitic fauna of the digestive tract of this host in the Western Alps and studying the dynamic of the most prevalent parasitic infections. Three coccidia (provisionally named Eimeria type 1, 2 and 3), two tapeworms (Dicrocoelium dendriticum and Ctenotaenia marmotae) and six nematodes (Ascaris laevis, Citellina alpina, Capillaria caudinflata, Ostertagia circumcincta/trifurcata, Nematodirusspathiger and an unidentified Spirurid) were found. C. marmotae, C. alpina and A. laevis appear as "dominant" species, whereas the other helminthes represent "capture" ones. Prevalence, intensity and relative abundance of these parasites are reported. C. caudinflata and N spathiger are signaled in M. marmota for the first time. A "spring rise" in Eimeria oocysts' output was demonstrated and the highest risks of infection were found in late spring for C. marmotae and in the middle of summer for A. laevis. Helminth parasites were absent or rare in young marmots.

INTRODUCTION

The parasitic fauna of the digestive tract of marmots (Marmota marmota) from French and Italian Alps has been poorly investigated (Blanchard, 1891; Blanchard and Blatin, 1907; Couturier, 1964; DSV, unpublished); hence the interest in realizing a first inventory relative to the Western Alps. The animals available in months which were little represented in the previous contributions (samples usually collected in September and October) and the possibility of integrating this material with the periodical collection of faeces, have enabled us to tackle the general dynamic aspects of parasitism which are worth particular attention in a species that hibernate for about 6 months a year.

Material and method

The digestive tract of 46 marmots, shot in the hunting season or otherwise recovered, has been examined according to the ordinary helminthological methods. The sample includes 16 males and 19 females in addition to 11 animals of undetermined sex; 6 animals are young of the year (age < 8 months), 11 are subadults (10-18 months) and 28 are adults (over 22 months). The origin of these marmots is reported in Fig. l. The helminths have been identified according to current keys (Skrjabin, 1951; Mozgovoi, 1953; Skrjabin 1954; Skrjabin et al., 1957) and original descriptions (Jettmar and Anschau, 1951). Moreover, the following surveys have been carried out:

- the qualitative examination (notation in a 33% solution of ZnS04) of 181 faecal samples from 23 valleys on the Italian side of the western Alps (mainly from the Valle d'Aosta region), at altitudes between 1.500 and 2.900 m;

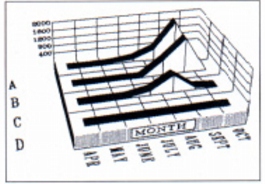

- the quantitative examination (Mc Master method) of 154 faecal samples collected, 15 to 30 days apart, in 4 areas with the characteristics given in Table 1. In both surveys, the size of feaces was such as to exclude their belonging to young marmots.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results are summarised in Tables 2 to 4 and in Figs. 3 and 6.

COCCIDIA - Oocysts of the genus Eimeria were found in 164 of 181 faecal samples (90.6%; Table 2). Non-sporulated oocysts could be divided into 3 different morphotypes (dimensions in mm ; Table 3):

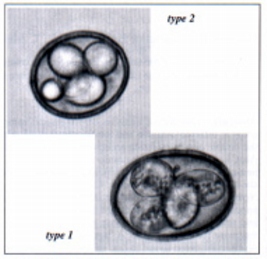

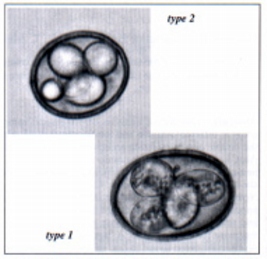

In the material preserved in 2% potassium dichromate solution, the above mentioned types corresponded to sporulated oocysts (Fig. 2) with the following characteristics (dimensions in mm):

None of these types corresponds to E. marmotae (Galli-Valerio, 1923) and E. arctomysi (Galli-Valerio, 1931), the two species, which are traditionally reported in M. marmota. According to the original descriptions (Galli- Valerio, 1923; Galli-Valerio, 1931), although poor and limited to the non-sporulated forms, differential elements may be detected as follows:

- in E. marmotae, the evident micropyle and the larger dimensions of oocyst (51 x 42 mm and sporont (33 mm in diameter).

- - in E. arctomysi; a micropyle which is clearly visible and sometimes prominent.

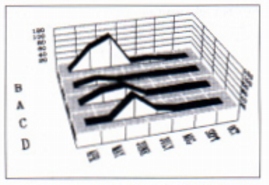

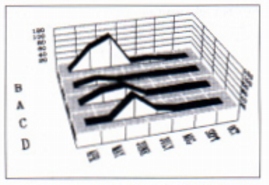

On the other hand, similarities exist the oocyst type 1 and E. tuscaroensis (Dorney, 1964), described in Marmota monax (Dorney, 1965), and between the oocyst type 2, E. monacis (Fish, 1930) and E. perforoides (Crouch and Becker, 1931), reported, the first in M. monax, bobac and sibirica, the second in M. monax only (Dorney, 1965; Levine and Ivens, 1965). Since a strict host specificity is attributed to Eimeria spp., cross infections between members of the Marmota genus will be necessary in order to correctly designate their coccidia. The shedding of oocysts, in particular of type 2 and 3, has been demonstrated from April 5 to October 11; it is worth stressing that, in the Gran Paradiso National Park, the surface activity of M. marmota extends, on average, from April 10-20 to October 10-20 (Peracino and Bassano, 1987). The presence of oocysts in the faeces of animals which have just emerged from their burrows makes the hypotheses of a winter persistence of the coccidial infection and of its ready re-activation from "dormant stages" acceptable, as demonstrated for E. zuernii in cattle (Euzeby, 1987). A spring peak of oocysis shedding was also demonstrated (Fig. 3, highest value of 172,800 oocysts/g of faeces) which, as in the "spring rise" of the nematodes, could promote the generational passage of infection. In the alpine environment, an increased spring shedding of Eimeria spp. Oocysts has been reported in the chamois (Trimaille, 1985). Nothing is known about the pathogenicity of coccidia in M. marmota; however, concurrence of a high number of oocysts, favourable environmental conditions for their sporulation and the newly born marmots leaving their burrows (between June and July; Huber, 1987) is an important premise for infection to be observed even in a clinical form.

TREMATODES - In the stomach and small intestine of a marmot, captured in Larche (Haute-Provence), four sexually mature (with eggs) specimens of Dicrocoelium dendriticum were found. No trematode was found in the liver of 34 of the marmots examined, among which was the above mentioned animals. The incidental character of the infestation, the limited number of specimens detected and their erratic site, make M. marmota an improbable host for this parasite in the area considered. In the Western Alps, and in Larche area itself, D. dentriticum is very common among domestic ruminants (especially ovines) and in Muflon (Sabatier, 1989; Cresci, 1992).

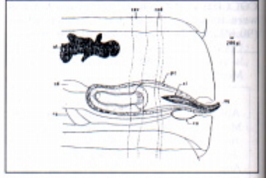

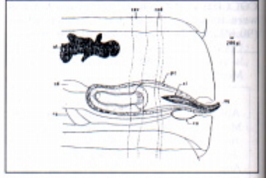

CESTODES - Table 4 highlights that Ctenotaenia marmotae (Froelich, 1802), an Anoplocephalan parasite of the small intestine, is a well represented species in our sample. The results of the copromicroscopic survey confirm that (Table 2) and demonstrate the fair reliability of the method used. An original drawing of C. marmotae is provided in Fig. 4. This tapeworm has been found in M. marmota several times, but also in M. bobac and M. baibacina (DSV, unpublished; Homing, 1969). In necropsies of May and June, the immature forms of C. marmotae were abundant (359specimens of 432 analysed, 83.1%). They are recognized easily by the thin caudal end, with proglottids having a more evident lengthwise development (Fig. 5), and by the narrower strobila (Table 5). However, no immature form was present in necropsies of September and October (235 specimens); the hibernating subjects, a subadult of April and four of the five youngs, which died between June and August, were free of C. marmotae (a single specimen, particularly immature, was present in the fifth). Eggs of C. marmotae were observed in the faeces from June 12 to October 9. On the basis of these data, of the intestinal vacuity of the hibernating marmot (Blanchard and Blatin, 1907; Couturier, 1963) and of an estimated pre-patent time of 40 days (analogy with other Anoplocephalidae) it is reasonable to assume that the risk of infestation by C. marmotae is particularly high at the end of April-beginning of May.

Considering the long evolution inside the intermediate host (at least l13 days at a temperature of18-20°C, (Ebermann, 1976), the parasitosis seems to be perpetuated mainly through cysticercoid larvae transmitted by Oribatid mites that became infested during the previous summer. Finally, the presence of eggs of C. marmotae in faeces collected in October seems to sit the time of intestinal "self-cure" either in the days immediately preceding retirement in the burrows or, as in Citellus citellus (Chute, 1964), in the first stages of hibernation; we believe that the atrophy of the intestine, which occurs in this period (in hibernating marmots the intestinal lumen is absolutely virtual), may cause, even on a simple physical basis, the removal of a parasite of considerable size, such as C. marmotae. Nothing is known about the pathogenicity of C. marmotae.

NEMATODES - Specimens belonging to 5 species have been collected: O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata in the stomach, Ascaris laevis, Capillaria caudinflata and Nematodirus spathiger in the small intestine and Citellina alpina in the cecum and large, intestine. Immature Spirurids, collected in the stomach, are also undergoing classification. A. laevis and C. alpina are the most common nematodes in the marmots examined (Table 4). A. laevis has been repeatedly reported, non only in M. marmota but also in North American Sciuridae such as M. monax, M. broweri and Citellus parryi (Horning, 1969); a close species, Ascaris tarbagan, is described in M. sibirica and in M. caudata (Mozgovoi, 1953). The morphological analysis of 3 of the 5 mature males available has enabled us to highlight characteristics which, according to the descriptions given in Mozgovoi, (1953), should pertain to both A. laevis (over 45 pairs of pre-anal papillae and, in two males, 5 pairs of post-anal papillae) and A. tarbagan (spicules measuring 520 to 560 mm in length, cloaca at 540-656 mm from the caudal end and, in one male, 6 pairs of post-anal papillae). The dimensions of the eggs found in the faeces (71-78 x 62-67 mm, N=50), would, in turn, fall within the range reported for A. tarbagan (Mozgovoi, 1953). These observations, together with the light morphological differentiation of these two ascarids and their unusual geographical distribution (in an area which extends from the Rocky Mountains to the Alps, through the mountain ranges of China and the former Soviet Union, A. laevis seems to be present only at the two for ends and A. tarbagan only in the central section), lead us to believe that the status of these parasites should be defined by means of refined methods of biochemical taxonomy. Due to the priority and by analogy with previous works on M. marmota (Horning, 1969), we prefer to maintain here the denomination A. laevis.As regards the pathogenicity of these nematodes, it has been reported that the presence of 75 to over 400 specimens of A. tarbagan is associated, in M. sibirica, with a stunted growth in the young and, in general, with a port build up of fat reserves which is likely to be incompatible with surviving the winter season (Dubinin, 1948). On the other hand, the parasitic loads that we detected (x = 1.86; range = 1-19) should be harmless, considering also that the infestation did non seem to concern the youngs, which, as a rule, are more sensitive to the pathogenic action of the ascarids (the only exception being the presence of 5 extremely immature parasites in an August young).

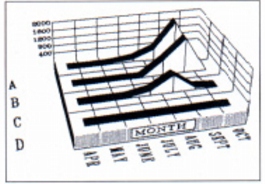

According to the prevalence trend and to the EPG values, as detected by copromicroscopy (Table 2 and Fig. 6) and assuming a pre-patent period of 36-40 days, as for A. tarbagan (Mozgovoi, 1953), A. laevis infestation occur during a period of at least 5 months (April-August), in which August seems to be particularly at risk (see rise of prevalences in September). Unfortunately, there is no supporting evidence regarding the period of exogenous development of A. laevis. Finally, eggs of ascarids have been detected in the faeces of M. marmota up to October 3, showing a rather late "self-cure" period. In M. sibirica, ascarids are gradually discharged during the last 2-3 weeks of surface activity (Dubinin, 1948).

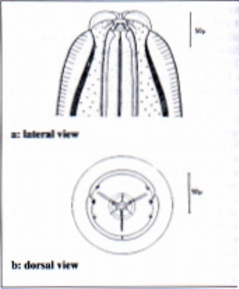

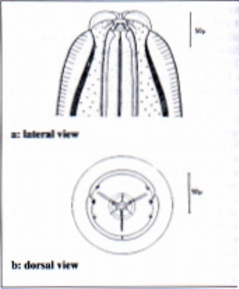

As opposed to A. laevis, C. alpina has been previously reported only once, still in M. marmota (Jettmar and Auschau, 1951); the epidemiological indexes in Table 4 show that this is a common, quantitatively "dominant" species, at least in the helminth community examined. Morphological details regarding mature specimens of C. alpina are given in Fig. 7 to integrate with the original drawings. The Citellina genus comprises 14 species, all described in Sciuridae and 6 of which are strictly specific to members of the Marmota genus (Hugot, 1980). This strict species-specificity has promoted the occurrence of co-evolution phenomena, to the extent that the phylogenesis of the Marmota genus, as reconstructed on the basis of paleontologic findings (Chaline and Mein, 1979), is totally parallel to the progressive differentiation of the cephalic structures of the members of the Citellina genus (Hugot, 1980).

Data available do net allow a satisfactory knowledge of the dynamic aspects of C. alpina infestation. As a matter of fact, since the copromicroscopic method used has proved to be unreliable (a single egg has been found in 181 faecal samples), the necessary integration of necropsy and copromicroscopic results is missing. We therefore confine ourselves to reporting the following:

- no parasites belonging to this genus were detected in 5 of 6 youngs (18 males and 20 immature females were present in a young of August);

- 4 of 6 adults/subadults of May and 19 of 22 adults/ subadults of June were infested, although mature females were detected only in 3 of the latter.

Nothing is known about the pathogenicity of C. alpina, although its saprovorous habits appear to limit its threat as a parasite.

O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata (experiments demonstrated that O. circumcincta is a polymorph species and that O. trifurcata represents one of its phenotypes (Lancaster et al., 1983), N. spathiger and C. caudinflata share low epidemiological indexes (Table 4); actually, these are species which are only occasionally present in M. marmota and are peculiar to other hosts present in their living space. O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata and N. spathiger are largely represented in the helminth fauna of sheep and goats, but also in chamois and ibex of the Western Alps (Balbo et al., 1978), while C. caudinflata is typical of the Galliformes, both domestic and wild (Skrjabin et al., 1957); among the latter, both Lyrurus tetrix and Alectoris graeca saxatilis may have come into contact with the infested marmot. N. spathiger (a mature female, identified on the basis of the eggs size and of the number of longitudinal cuticular ridges) and C. caudinflata (a mature female, classified mainly on the basis of the morphology of the vulvar region) have been reported for the first time in M. marmota. Specimens of Capillaria sp. had been previously collected in a marmot from the Freiburg area (Horning, 1969). The finding of O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata (a total of 14 females, one male with circumcincta phenotype and 2 males with trifurcata phenotype) has a precedent in 2 marmots of the Gran Paradiso National Park (Cancrini et al., 1981). The tendency of M. marmota to host "capture" helminthic species is confirmed by the results of the copromicroscopy (presence of strongyliform eggs in 14 samples and of Trichuris sp. eggs in another 2) and by other reports of "Trichostrongylidae", even if in generic terms (Horning, 1969; Kreis, 1962).

The Spirurids (N=37) detected in the stomach of 6 marmots, two of which hibernating, are also likely to be "capture" nematodes. However, this is the first time that helminths have been reported in the digestive tract of hibernating marmots. The presence of these nematodes in the stomach, the only section maintaining an actual lumen during hibernation, is a new element, which supports the hypothesis (see CESTODES) according to which the autumn self-cure should be primed by essentially physical stimuli. Eggs of Spirurids had been previously reported in the faeces of Swiss marmots (Horning, 1969).

CONCLUSIONS

Our investigations show that the gastro-intestinal parasitic fauna of M. marmota, although it has been the subject of several contributions, still has wide "shadow areas", regarding taxonomic aspects (systematics of Eimeria spp. and of A. laevis) and also the life cycle, epidemiology and pathogenicity of a good part of the agents found. In the material analysed, 6 quantitatively "dominant" species emerge (A laevis, C. marmotae, C. alpina, Eimeria sp type 1, 2 and 3), which each individual marmot has a high probability to host during its active life span. With the exception of C. alpina, and, to a certain extent, of Eimeria sp, type 1, the evolutive chronology of these species has been outlined for the study area.

Compared to the gastro-intestinal parasitic fauna of other mountain herbivores, we would like to emphasize, as peculiar elements, the marginal role of the youngs as targets and/or recipients of helminth infections and the tendency of M. marmota to host, with relative frequency, "capture" helminths from hosts which can even be quite far apart in the zoological scale. Finally, it is interesting to note, from a speculative point of view, the detection of nematodes in the digestive tract of hibernating subjects.

ritorno/back

PARASSITI GASTRO-INTESTINALI DI Marmota marmota NELL'ARCO ALPINO OCCIDENTALE

Bassano B.*, Sabatier B.**, Rossi L.*, Macchi E.*

* Depart. Produzioni Animali, Epidemiologia ed Ecologia, University of Torino, Via Nizza 52, 10126 Torino (I)

** Veterinarian, 322 Rue Chaudun, St. Jean Maurienne (F)

Introduzione

Le indagini sulla parassitofauna del tratto digerente di marmotte (Marmota marmota) provenienti dall'arco alpine francese ed italiano sono poco numerose e a carattere puntuale (Blanchard, 1891; Blanchard and Blatin, 1907; Couturier, 1964; DSV, non pubblicato); di qui l'interesse per la realizzazione di un primo inventario relative alle Alpi Occidentali. La disponibilità di materiale autoptico raccolto in periodi scarsamente rappresentati nei precedenti contributi (i capi sinora esaminati derivavano, in massima parte, da prelievi effettuati in settembre ed ottobre) e la possibilità di integrare detto materiale con la raccolta periodica di feci, ci hanno poi consentito di affrontare aspetti generali di dinamica del parassitismo che, in una specie ibernante per ca. 6 mesi all'anno, sono meritevoli di particolare attenzione.

Materiali e metodi

È é stato esaminato, secondo le tecniche usuali di ricerca elmintologica, il tratto digerente di 46 marmotte, decedute nel corsa di operazioni di cattura, abbattute durante la caccia o altrimenti recuperate. il campione annovera 16 maschi e 19 femmine, oltre a 11 soggetti per i quali non È stato possibile risalire al sesso; 6 animali sono giovani dell'anno (età < 8 mesi), 11 sono subadulti (10-18 mesi) e 28 adulti (oltre 22 mesi). La provenienza dei capi esaminati è riportata in Fig. 1. Gli elminti raccolti sono stati identificati secondo chiavi correnti (Skrjabin, 1951; Mozgovoi, 1953; Skrjabin 1954; Skrjabin et al., 1957) e descrizioni originali (Jettmar e Anschau, 1951). Inoltre, si sono eseguiti esami copromicroscopici:

- qualitativi (per affioramento) in soluzione al 33% di ZnS04) su 181 campioni fecali di marmotta provenienti da 23 vallate del versante italiano delle Alpi Occidentali (principalmente Valle d'Aosta), a quote comprese fra 1500 e 2900 m;

- quantitativi (con metodo di Mcmaster) su 154 campioni fecali di marmotta raccolti, con cadenza da quindicinale a mensile, in 4 aree campione con le caratteristiche indicate in Tab. 1.

Nelle due serie di esami si sono analizzate feci con dimensioni che permettevano di escluderne l'appartenenza a soggetti dell'anno.

Risultati e discussione

I risultati sono compendiati nelle Tab. 2-4 e nelle Figg. 3 e 6.

COCCIDI - Oocisti del genere Eimeria sono state rinvenute in 164 dei 181 campioni fecali esaminati (90.6%; Tab. 2). Nel materiale fresco erano presenti oocisti non sporulate morfologicamente raggruppabili in 3 tipologie (dimensioni in mm) :

A queste 3 tipologie corrispondevano, nel materiale conservato in soluzione di bicromato di K al 2%, oocisti sporulate (Fig. 2) con le seguenti caratteristiche (dimensioni in mm) :

Nessuna di queste tipologie corrisponde a quella di E. marmotae (Galli-Valerio, 1923) e di E. arctomysi (Galli-Valerio, 1931 ), le due specie classicamente segnalate in M. marmota. Dalle descrizioni originali (Galli-Valerio, 1923; Galli-Valerio, 1931), pur carenti e limitate alle forme asporulate, si possono infatti ricavare gli elementi differenziali che seguono:

- in E. marmotae, l'evidente micropilo e le maggiori dimensioni di oociste (51 x 42 mm) e sporonte (diametro di 33 mm) ;

- in E. arctomysi, il micropilo ben visibile e talora prominente.

Al contrario, esistono analogie fra le oocisti di tipo 1 ed E. tuscaroensis Dorney , 1965, descritta in Marmota monax (Dorney, 1965), e fra le oocisti di tipo 2, E. monacis Fish, 1930 ed E. perforoides Crouch and Becker, 1931, segnalate la prima in M. monax, bobac e sibirica, la seconda nella sola M. monax (Dorney, 1965; Levine, lvens, 1965); poichè ad Eimeria spp. viene riconosciuta una stretta specificità d'ospite, prove di infezione crociata nell'ambito del genere Marmota si renderanno necessarie ai fini di una corretta denominazione dei coccidi trovati. L'eliminazione di oocisti, del tipo 2 e 3 in modo particolare, è stata dimostrata dal 05.04 al 11.10; ricordiamo che nel Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso il periodo di attività di M. marmota si estende, in media, dal 10-20.04 ai 6-20.10 (Peracino, Bassano, 1987). La presenza di oocisti nelle feci di animali appena fuoriusciti dalle tane rende ammissibile l'ipotesi della persistenza invernale dell'infezione e della sua pronta riattivazione a partire da "forme di attesa", come dimostrato per E. zuemii del bovino (Euzeby, 1987). lnteressante è anche l'evidenziazione di un picco di eliminazione primaverile di oocisti (Fig. 3; valore record di 172.800 oocisti/g di feci) che, come nel caso dello "spring rise " dei nematodi, potrebbe favorire il passaggio generazionale dell'infezione. In ambiente alpine, un'accresciuta eliminazione primaverile di Eimeria spp. è stata segnalata nel camoscio (Trimaille, 1985). Nulla si sa interna al potere patogeno dei coccidi in M. marmota; tuttavia, la concomitanza fra numero elevato di oocisti, condizioni ambientali favorevoli alla loro sporulazione e fuoriuscita dalle tane dei nuovi nati (a cavallo fra giugno e luglio (Huber, 1987) crea i presupposti a che l'infezione passa estrinsecarsi anche in forma clinica.

TREMATODI - Nello stomaco e nell'intestine tenue di un soggetto, catturato a Larche (Haute-Provence), erano presenti quattro esemplari sessualmente maturi (con uova) di Dicrocoelium dendriticum. Nessun tramatode è stato invece trovato nel fegato di 34 delle marmotte esaminate, fra cui il soggetto di cui sopra. Il carattere occasionale dell'infestazione, il numero limitato di esemplari rinvenuti e la loro sede erratica fanno di M. marmota un improbabile serbatoio di questo parassita nell'area di studio. Sulle Alpi Occidentali, e nella stessa zona di Larche, D. dendriticum è assai comune fra 1 ruminanti domestici (ovini in particolare) e nel Muflone (Sabatier, 1989; Cresci, 1992).

CESTODI - Dalla Tab. 4 si evidenzia come Ctenotaenia marmotae (Froelich, 1802), Anoplocephalidae parassita dell'intestino tenue, sia specie ben rappresentata nel nostro campione. I risultati degli esami copromicroscopici confermano quanto sopra (Tab.2) e testimoniano la discreta attendibilità della tecnica impiegata. C. marmotae, di cui si fornisce un disegno originale(Fig. 4), è stata più volte segnalata in M. marmota, ma anche in M. bobac e M. baibacina (DSV non pubblicato; Horning, 1969).

Nel materiale autoptico relativo ai mesi di maggio e giugno erano abbondanti le forme immature di questo cestode (359 esemplari su 432 esaminati, pari all'83.1%), facilmente riconoscibili "a fresco " per l'estremità posteriore assottigliata, con proglottidi a maggior sviluppo longitudinale (Fig. 5), e per la minor larghezza dello strobila (Tab. 5). Nessuna forma immatura era invece presente nel materiale autoptico relative ai mesi di settembre ed ottobre (2,15 esemplari), mentre erano indenni da C. marmotae i tre soggetti ibernanti, un subadulto di aprile e quattro dei cinque giovani dell'anno venuti a morte fra giugno ed agosto, (nel quinto era presente un unico esemplare fortemente immaturo). Uova di C. marmotae sono comparse nelle feci a partire dal 12.06 e fino al 09.10. Sulla base di questi elementi, della ben nota vacuità intestinale della marmotta ibernante (Blanchard e Blatin, 1907; Couturier, 1963) e di una prepatenza di C. marmotae stimabile in 40 gg ca. (per analogia con altri Anoplocephalidae), è ragionevole ipotizzare che il rischio di infestazione sia particolarmente elevato a fine aprile-maggio. Inoltre, la lunga evoluzione all'interno dell'ospite intermedio (almeno 113 gg alla temperatura di 18-20°C (Ebermann, 1976), fa ritenere che la parassitosi si perpetui, essenzialmente, tramite larve cisticercoidi veicolate da acari Oribatidi, infestatisi nell'estate precedente. Da ultime, la presenza di uova di C. marmotae in feci raccolte ad ottobre sembra collocare il momento del " self-cure " intestinale o nei giorni immediatamente precedenti la chiusura delle tane e/o, come in Citellus citellus (Chute,1964), nelle prime fasi dell’ibernazione; riteniamo che l'atrofia del tubo digerente ed il collabimento delle pareti intestinali che si determinano in questo periodo (nel soggetto ibernante il lume intestinale è assolutamente virtuale), possano comportare, anche su semplice base fisica, l'espulsione di un parassita di massa considerevole, quale appunto C. marmotae. Nulla si sa intorno al potere patogeno di C. marmotae.

NEMATODI - Sono stati raccolti esemplari di 5 specie: O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata nello stomaco, Ascaris laevis, Capillaria caudinflata e Nematodirus spathiger nell'intestino tenue e Citellina alpina nel cieco e nel grosso intestino. Spiruridi immaturi, raccolti a livello gastrico, sono inoltre in corso di classificazione. A. laevis e C. alpina sono 1 nematodi di più comune reperimento nei soggetti da noi esaminati (Tab.4).

A. laevis è specie ripetutamente segnalata non solo in M. marmota ma anche in Sciuridi nord-americani, quali M. monax., M. broweri e Citellus parryi (Horning, 1969); una specie assai prossima, Ascaris tarbagan, è invece descritta in M. sibirica e in M. caudata (Mozgovoi, 1953). Lo studio morfologico di 3 dei 5 maschi maturi a nostra disposizione ci ha permesso di evidenziare caratteri che, stando alle descrizioni di cui in (Mozgovoi, 1953), sarebbero propri ora di A. laevis (oltre 45 paia di papille preanali e, in due maschi, 5 paia di papille post-anali) ora di A tarbagan (spiculi di lunghezza compresa fra 520 e 560 mm, cloaca a 540-656 mm dall'estremità caudale e, in un maschio, 6 paia di papille postanali). Le dimensioni delle uova trovate nelle feci (71 -78 x 62-67 mm, N=50), a loro volta, ricadrebbero nel range riportato per A. tarbagan (Mozgovoi, 1953). Questi rilievi, accanto alla modesta differenziazione morfologica delle due specie di ascaridi in questione e ad una distribuzione geografica quanta mena insolita delle stesse (nell'ambito di un areale che si estende dalle Montagne Rocciose alle Alpi, attraverso i sistemi montuosi della Cina e dell'ex Unione Sovietica, A. laevis sarebbe presente solo ai due estremi ed A. tarbagan solo nella parte centrale), ci inducono a ritenere che lo status di questi parassiti andrebbe precisato col ricorso a tecniche di indagine più raffinate. In questa sede, per ragioni di priorità e per analogia con precedenti contributi relativi a M. marmota (Horning, 1969), preferiamo mantenere il binomio A. laevis.

Relativamente al potere patogeno di questi nematodi, è segnalato che la presenza di 75 fino ad oltre 400 esemplari di A. tarbagan si associa, in M. sibirica, a crescita stentata dei giovani e ad accumuli di grasso in quantità verosimilmente incompatibile col superamento dell'inverno (Dubinin, 1948). Invece, le cariche parassitarie da noi trovate (x= 1.86; range= 1-19) non dovrebbero essere di nocumento, tante più che l'infestazione non è sembrata interessare i soggetti dell'anno, di regola più sensibili all'azione patogena degli ascaridi (unica eccezione la presenza di 5 parassiti fortemente immaturi in un piccolo di agosto).

Stando all'andamento delle prevalenze e dei valori UPG, rilevati tramite copromicroscopia (Tab. 2 e Fig. 6) e ipotizzando un periodo di prepatenza di 36-40 gg., come per A. tarbagan (Mozgovoi, 1953), si puoi dedurre che l'infestazione da A. laevis venga contratta lungo un arco di almeno 5 mesi (aprile-agosto), fra i quali ago sto sembra essere particolarmente a rischio (vedi impennata delle prevalenze in settembre). Purtroppo, non esistono dati di supporta relativi ai tempi dello sviluppo esogeno di A. laevis. lnfine, uova di ascaridi sono state evidenziate nelle feci di M. marmota fino alla data del 03.10, a testimonianza di un "self cure " piuttosto tardivo. In M. sibirica, gli ascaridi vengono gradualmente espulsi nelle ultime 2-3 settimane di attività in superficie (Dubinin, 1948).

Diversamente da A. laevis, esiste un'unica precedente segnalazione di C. alpina, anch'essa in M. marmota (Jettmar e Anschau, 1951); gli indici epidemiologici in Tab. 4 dimostrano peraltro che trattasi di specie comune e quantitativamente"dominante", quanto meno nell'ambito della popolazione elmintica considerata. Dettagli morfologici relativi ad esemplari maturi di C. alpina vengono riportati in Fig.7, a integrazione della descrizione originale. Il genere Citellina consta di 14 specie, tutte descritte in Sciuridae e 6 delle quali strettamente specifiche per rappresentanti del genere Marmota (Hugot, 1980). Questa stretta specie-specificita ha favorite la comparsa di fenomeni di coevoluzione, al punto che la filogenesi del genere Marmota quale ricostruita in base a reperti paleontologici (Chaline and Mein, 1979), trova totale parallelismo nel progressivo differenziarsi delle strutture cefaliche nei diversi rappresentanti del genere Citellina (Hugot, 1980).

I dati a nostra disposizione non consentono di inquadrare in modo soddisfacente gli aspetti dinamici dell'infestazione da C. alpina. Infatti, poiché il metodo di ricerca copromicroscopica da noi adottato si è rivelato inattendibile (un singolo uovo è stato trovato in 181 campioni fecali), è venuta meno la necessaria integrazione fra i risultati delle indagini necroscopiche e copromicroscopiche. Ci limitiamo pertanto a segnalare che non erano presenti parassiti di questo genere in 5 dei 6 giovani dell'anno (in un giovane di agosto erano invece presenti 18 maschi e 20 femmine immature), e che erano infestati 4 dei 6 adulti/subadulti di maggio e 19 dei 22 adulti/subadulti di giugno, anche se femmine mature sono state rinvenute solo in 3 di questi ultimi. Nulla è noto intorno al potere patogeno di C. alpina, anche se le abitudini verosimilmente detriticole sembrano farne un parassita scarsamente temibile. O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata (è stato sperimentalmente dimostrato che O. circumcincta è specie polimorfa e che O. trifurcata ne rappresenta un fenotipo (Lancaster et al., 1983), N. spathiger e C. caudinflata sono accomunate da indici epidemiologici bassi (Tab.4); in effetti, trattasi di specie solo occasionalmente presenti in M. marmota e proprie di altri ospiti che ne condividono la spazio vitale. O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata e N. spathiger sono abbondantemente rappresentate nell'elmintofauna di ovini, caprini ma anche di camosci e stambecchi delle Alpi Occidentali (Balbo et al., 1978), mentre C. caudinflata è tipica dei Galliformi, tanto domestici come selvatici (Skrjabin et al., 1957); fra questi ultimi possono aver avuto contatti con la marmotta infestata sia Lyrurus tetrix sia Alectoris gracca saxatilis. N. spathiger (una femmina matura, identificata in base alle dimensioni delle uova ed al numero delle creste cuticolari longitudinali) e C. caudinflata (una femmina matura, classificata principalmente in base alla morfologia della regione vulvare) vengono segnalate per la prima volta in M. marmota. Esemplari di Capillaria sp. erano stati precedentemente raccolti in una marmotta del Friburghese (Horning, 1969). Il reperto di O. circumcincta/O. trifurcata (in totale 14 femmine, un maschio con fenotipo circumcincta e 2 maschi con fenotipo trifurcata) ha un precedente in 2 marmotte del Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso (Cancrini et al., 1981). La propensione di M. marmota ad albergare specie elmintiche cd. "di cattura " trova conferma nei risultati della copromicroscopia (presenza di uova strongiliformi in 14 campioni e di uova di Trichuris sp. in altri 2) e nelle pur generiche segnalazioni di "Trichostrongylidae " di cui in Horning (1969) e Kreis (1962). E probabile che "di cattura" debbano considerarsi anche gli Spiruridi (N= 37) rinvenuti nello stomaco di 6 soggetti, due dei quali ibernanti; sottolinieamo, a quest'ultimo proposito, come si tratti della prima segnalazione di elminti nel tratto digerente di marmotte in letargo. La presenza di nematodi nello stomaco, unico segmenta che mantiene un lume reale anche durante l'ibernazione, costituisce elemento a favore dell'ipotesi precedentemente avanzata (cfr. CESTODI), secondo cui l'autodisinfestazione autunnale sarebbe innescata da stimoli essenzialmente fisici. Uova di Spiruridi erano state segnalate nelle feci di marmotte svizzere (Horning, 1969).

Conclusioni

Le nostre indagini evidenziano che la parassitofauna gastro-intestinale di M. marmota, per quanto oggetto di un numero non trascurabile di contributi, presenta ancora ampie "zone d'ombra", sia sotto il semplice profila tassonomico (sistematica di Eimeria spp. e di A. laevis), sia per quanto riguarda il ciclo biologico, l'epidemiologia e il potere patogeno di buona parte degli agenti individuati.

Nel materiale da noi esaminato emerge la presenza di 6 specie quantitativamente "dominanti" (A. laevis, C. marmotae, C. alpina, Eimeria sp. Di tipo 1, 2 e 3), che ciascun individuo ha elevate probabilità di albergare nel corso della vita in superficie. Con l'eccezione di C. alpina e, in certa misura, di Eimeria sp. tipo 1, la cronologia evolutiva di queste specie è stata sostanzialmente delineata per l'area di studio.

Come elementi di peculiarità rispetto alla parassitofauna gastro-intestinale di altri erbivori di montagna, vanno sottolineati il ruolo marginale dei soggetti dell'anno come bersaglio e/o serbatoio di infestazioni elmintiche e la tendenza di M. marmota ad albergare, con relativa frequenza, elminti cd."di cattura", propri di ospiti anche assai distanti nella scala zoologica. Interessante, da un punto di vista speculativo, è infine il reperto di nematodi nel tratto digerente di soggetti ibernanti.

ritorno/back

Table 1: Copromicroscopic survey of M. marmota in the Western Alps: characteristics of the sample areas.

|

Sample area |

Valley |

Altitude (mts) |

First sighting of a marmot post hibern. |

Last sighting of a marmot before hibern. |

Faecal exams |

|

A |

Orco |

1600 |

25-26 Mar |

1-5 Oct |

83 |

|

B |

Susa |

1800 |

5-l0 Apr |

3-4 Oct |

21 |

|

C |

Ayas |

2100 |

20-25 Apr |

5-9 Oct |

27 |

|

D |

Ayas |

2300 |

25-30 Apr |

5-9 Oct |

23 |

ritorno/back

Table 2: Examination of faeces of M. marmota for protozoan oocysts and helminth eggs: overall and monthly prevalence (Eim=Eimeria spp.; AL=A. laevis; CM=C. marmotae; CA=C. alpina; TRI=Trichuris sp.; TS=Trichostrongylidae).

|

Month |

Faecal Samples |

% positive for |

| |

|

Eim |

AL |

CM |

CA |

TRI |

TS |

|

Apr |

16 |

81.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

May |

30 |

90.0 |

6.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

13.3 |

|

]un |

21 |

95.2 |

23.8 |

38.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

33.3 |

|

Jul |

29 |

93.1 |

34.4 |

68.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Aug |

34 |

94.1 |

38.2 |

58.8 |

2.9 |

5.8 |

0.0 |

|

Sep |

35 |

88.5 |

62.5 |

54.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

8.5 |

|

Oct |

16 |

87.5 |

50.0 |

31.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

TOT |

181 |

90.6 |

32.0 |

39.7 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

7.7 |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

shape |

elliptic |

elliptic |

subspherical |

|

length |

34-37 |

22-27 |

18-20 |

|

width |

25-29 |

18-23 |

18-20 |

|

micropyle |

absent |

absent |

absent |

|

wall colour |

yellow-brown |

clear |

clear |

|

wall thickness |

thick |

thin |

thin |

|

wall surface |

rough |

smooth |

smooth |

|

sporont diameter |

16-18 |

11- 12 |

10-12 |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

sporocyst shape |

lemon |

oval |

suboval |

|

Stieda body |

present |

present |

absent |

|

sporocyst length |

15-17 |

8.5-10 |

6.2-7.1 |

|

sporocyst width |

9-11 |

5.5-7.0 |

4.9-5.7 |

|

oocystic residue |

absent |

present |

present |

|

polar granules |

present |

present |

present |

|

sporocystic residue |

present |

present |

present |

|

sporulation time (days) |

>30 <60 |

<7 |

<7 |

ritorno/back

Table 3: Helminthological survey of 46 marmots of the Western Alps: rough data (A=adult; S=subadult or yearling; Y=young; *=Provinces or Departments; AL=A. laevis; CM=C. marmotae; CA=C. alpina).

|

N |

Age |

Sex |

Month |

Origin* |

AL |

CM |

CA |

Others |

|

1 |

Y |

M |

Jan |

Cuneo |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

S |

M |

Jan |

Cuneo |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Spiruridae (3) |

|

3 |

A |

F |

Jan |

Cuneo |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Spiruridae (1) |

|

4 |

S |

ND |

Apr |

Torino |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

5 |

S |

ND |

May |

Torino |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

6 |

A |

F |

May |

Aosta |

0 |

36 |

0 |

0 |

|

7 |

S |

M |

May |

Savoie |

0 |

44 |

477 |

0 |

|

8 |

S |

M |

May |

Savoie |

0 |

49 |

26 |

0 |

|

9 |

A |

M |

May |

Savoie |

0 |

169 |

350 |

0 |

|

10 |

A |

M |

May |

Savoie |

0 |

67 |

187 |

0 |

|

11 |

A |

F |

Jun |

Aosta |

0 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

|

12 |

S |

F |

]un |

Aosta |

0 |

15 |

18 |

0 |

|

13 |

A |

F |

]un |

Aosta |

0 |

>200 |

>200 |

0 |

|

14 |

A |

F |

]un |

Aosta |

2 |

20 |

2 |

0 |

|

15 |

Y |

ND |

]un |

Torino |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

16 |

A |

ND |

]un |

Torino |

17 |

4 |

0 |

C. caudinflata (1) |

|

17 |

S |

ND |

]un |

Torino |

7 |

0 |

26 |

Spiruridae (5) |

|

18 |

A |

F |

]un |

Torino |

0 |

22 |

0 |

0 |

|

19 |

S |

M |

]un |

Cuneo |

12 |

42 |

620 |

0 |

|

20 |

A |

F |

]un |

H. Provence |

0 |

91 |

22 |

D. dendriticum (4) |

|

21 |

A |

F |

]un |

H. Provence |

1 |

10 |

43 |

0 |

|

22 |

A |

M |

]un |

H. Provence |

6 |

40 |

11 |

O. circumcincta (1) |

|

23 |

A |

F |

]un |

H. Provence |

2 |

90 |

114 |

O. trifurcata (16) |

|

24 |

A |

M |

]un |

H. Provence |

0 |

32 |

382 |

0 |

|

25 |

A |

M |

]un |

H. Provence |

7 |

397 |

8 |

0 |

|

26 |

A |

F |

]un |

H. Provence |

0 |

262 |

93 |

0 |

|

27 |

A |

M |

]un |

H. Provence |

0 |

130 |

122 |

0 |

|

28 |

A |

F |

]un |

H. Provence |

0 |

103 |

53 |

0 |

|

29 |

A |

F |

Jul |

Aosta |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

30 |

S |

ND |

Jul |

Aosta |

0 |

2 |

15 |

spiruridae (1) |

|

31 |

A |

F |

Jul |

H. Provence |

2 |

249 |

27 |

|

|

32 |

A |

F |

Jul |

H. Provence |

1 |

464 |

91 |

|

|

33 |

A |

M |

Jul |

H. Provence |

0 |

197 |

229 |

|

|

34 |

Y |

ND |

Jul |

H. Provence |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

35 |

Y |

ND |

Jul |

H. Provence |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

36 |

A |

M |

Jul |

H. Provence |

0 |

101 |

206 |

|

|

37 |

A |

F |

Jul |

H. Provence |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0 |

|

38 |

Y |

M |

Aug |

Torino |

5 |

0 |

28 |

0 |

|

39 |

Y |

M |

Aug |

Cuneo |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

40 |

S |

F |

Sep |

Torino |

0 |

149 |

12 |

Spiruridae (26) |

|

41 |

A |

ND |

Sep |

Torino |

6 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

42 |

A |

F |

Sep |

Aosta |

19 |

31 |

0 |

0 |

|

43 |

A |

ND |

Sep |

Cuneo |

0 |

3 |

15 |

Spiruridae (1) / N. spathiger (1) |

|

44 |

A |

M |

Oct |

Savoie |

0 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

|

45 |

S |

ND |

Oct |

Aosta |

0 |

5 |

53 |

0 |

|

46 |

Y |

M |

Oct |

Torino |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

ritorno/back

Table 4: Helminths of the digestive tract of M. marmota: epidemiological indexes (P=prevalence; I=intensity or mean number of parasites per host; AR=relative abundance or % of a parasite species in the helminth community).

|

Species |

N. Infected |

P |

I |

AR |

Range |

|

Ascaris laevis |

14 |

30.4 |

1.86 |

1.29 |

1-19 |

|

Capillaria caudinflata |

1 |

2.1 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

1 |

|

Citellina alpina |

28 |

60.8 |

73.47

|

51.56

|

2-620

|

|

Ctaenotaenia marmotae

|

36

|

78.2

|

66.10

|

46.49

|

2-464

|

|

Dicrocoeliun dendriticum |

1 |

2.2 |

0.08 |

0.06 |

4 |

|

Nematodirus spathiger |

1 |

2.2 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

1 |

|

0stertagia circumcincta/Ostertagia trifurcata |

2 |

4.3 |

0.32 |

0.22 |

1-16 |

|

Spiruridae |

6 |

13.0 |

0.82 |

0.57 |

1-26 |

ritorno/back

Table 5: Total length and width of mature and immature specimen of C. marmotae (measures in mm).

|

|

Mature (N=94) |

Immature (N=114) |

|

|

|

|

Length |

x |

111.19 |

78.12 |

| |

s.d. |

63.33 |

88.17 |

| |

range |

(40-330) |

(10-330) |

| |

|

|

|

|

Width |

x |

12.51 |

4.15 |

| |

s.d. |

2.12 |

3.06 |

| |

range |

(8-18) |

(0.5-11) |

ritorno/back

Fig. 1: Origin of the marmots necropsied

ritorno/back

Fig. 2: Sporulated oocysts of Emeira sp. type 1 (right) and Emeira sp. type 2 (left)

ritorno/back

Fig. 3: Dynamic of Eimera oocysts shedding in four sample areas of the Western Alps (numbers in thousands)

ritorno/back

Fig. 4: Detail of the genital apparatus of Ctenotaenia marmotaea - genital atrium; cd - vas deferens; ced ñ dorsal excretory vessel; cev - Ventral excretory vessel; ci - cirrus; pc - cirrus sac; rs - receptaculum seminis; ut - uterus; va - vagina; vsi - inner seminal vesicule

ritorno/back

Fig. 5: Caudal end of immature specimens of C. marmotae

ritorno/back

Fig. 6: Dynamic of ascarid ova shedding in four sample areas of the Western Alps

ritorno/back

Fig. 7: Anterior end of Citellina alpina

ritorno/back

References

BALBO T., COSTANTINI R., LANFRANCHI P. & GALLO M.G. (1978). Parassitologia, 20, 1-3, 131-137.

BLANCHARD R. (1891). Mem. Zool. France, 4: 420-489.

BLANCHARD R. & BLATIN M. (1907). Arch. Parasit., ii (3): 361-378.

CANCRINI G., LANFRANCHI P. & [OR[ A. (1981). Parassitologia, 23: 147-148.

CHALINE J & MEIN P. (1979). "Les Rongeurs et l'évolution". Doin Ed., Paris, 325 pp.

CHUTE R.M. (1964). Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Series A, Iv. Biologica, 71/7: 115-122.

COUTURIER M.J.A. (1963). Mammalia, 27 (4): 455-482.

COUTURIER M.J.A. (1964). "Le gibier des montagnes françaises". Arthaud Ed., Grenoble, 471 pp.

CRESCI M.E. (1992). Thesis Fac. Med. veter. Tonna, 177 pp.

Direction Services vétérinaire (DSV) Savoie. Annual reports 1985/88 (unpublished).

DORNEY R.S. (1965). J. Protozool., 12 (3): 423-426.

DUBININ v.B. (1948). Trudy Voenno-Meditsinkoi Akademii, 64: 87-101.

EBERMANN E. (1976). Z. Parasitenk., 50: 303-312.

EUZEBY J. (1987). "Protozoologie Médicale Comparée", vol. II. Collec. Fondat. Mérieux Ed., Lyon, 430 pp.

GALLI-VALERIO B. (1923). Zbl. Bakt., ( Orig., 91: 120125.

GALLI-VALERIO B. (1931). Zbl. Bakt., I, Orig., 129: 98-106.

HORNING B. (1969). Jahrbuck des Naturhistorischen Museums der Stadt Bern, 1966/68: 137-200.

HUBER W. (1987). "La Marmotte des Alpes". Office National Chasse Ed., Paris, 34 pp.

HUGOT J.P. (1980). Annales de Parasitologie, 55, 1: 97-109.

JETTMAR H.M. & ANSCHAU M. (1951). Z. Tropenmed. Parasit., 2: 412-428.

KREIS H.A. (1962). Schweiz. Arch. Tierheil., 104: 94-115 & 169-194.

LANCASTER M.B., HONG C. & MICHEL J.F. (1983). in Stone E.R, Platt H.M. & Khalil L.F. (Eds): "Concepts in nematode systematics". London Academic Press Ed., London: 293-302.

LEVINE N.D. & IVENS v. (1965). "The Coccidian parasites (Protozoa, Sporozoa) of Rodents". Illinois. Biological Monographs, 33, The University of Illinois Ed., Urbana, 357 pp.

MOZGOVOI A.A. (1953). "Ascaridata of Animais and Man and the Diseases caused by Them", Part 1. The Academy of Sciences of USSR Ed., Moscow, 390 pp.

PERACINO v. & BASSANO B. (1987). "La Marmotta Alpina". Ente Parco Naz. Gran Paradiso Ed., Tonna, 40 pp.

SABATIER B. (1989). Thesis Ecole Nat. veter. Lyon, 178 pp.

SKRJABIN Ks., SHIKHOBALOVA N.P. & ORLON I.v. (1957). "Trichocephalidae and Capillariidae of Animals and Man and the Diseases Caused by Them". The Academy of Sciences of USSR Ed., Moscow, 599 pp.

SKRJABIN K.1. (1951). "Essentials of Cestodology", vols. The Academy of Sciences of USSR Ed.,

. Moscow, 549 pp.

SKRJABIN K.1. (1954). "Essentials of Nematodology", vols II. The Academy of Sciences of USSR Ed., Moscow, 704 pp.

TRIMAILLE J.C. (1985). Thesis Ecole Nat. veter. Lyon, 126 pp.

ritorno/back

Tornare index / back contents