Bassano B., Durio P., Gallo Orsi U., Macchi E

eds., 1992. Proceedings of the 1st Int. Symp. on

Alpine Marmot and genera Marmota. Torino.

Edition électronique, Ramousse R., International Marmot Network, Lyon 2002

HELMINTH COMMUNITY ON ALPINE MARMOTS

Manfredi M.T. *, Zanin E. **, Rizzoli A.P. *

*Istituto Patologia Generale, Facoltà di Medicina Veterinaria, Università degli studi di Milano;

**Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie, sezione di Trento.

Abstract - The helminth infracommunity of marmots from Eastern Alps was studied. All the animals were infected. Ctenotaenia marmotae (Cestoda: Anoplocephalidae) and Citellina alpina (Nematoda: Oxyuridae) were regarded as core species and had the highest values for prevalence (P= 75% and P= 65%) and abundance (A= 21J and A= 211). We also discuss the effects of C. marmotae on infracommunity structure.

INTRODUCTION

Although a number of surveys have been done little is known about the hierarchical structure of the gastrointestinal helminth infracommunity of Marmota marmota, rodent Sciurida. The most comprehensive review of ectoparasites and endoparasites of the Alpine marmot is that of Sabatier (1989). Several factors may affect helminth abundance and diversity.

Behaviour, vagility, diet and the host habitat are of special importance. Community diversity can also be related to potential helminth-helminth interaction. It has been observed that cestodes and acanthocephalans are often dominant in helminth enteric communities, because of their ability to absorb nutrients directly through their body surfaces (Smyth, 1969).

Dioecocestus asper (a large cestode) was found to be dominant in the infracommunity of red-necked grebes (Podiceps grisegena) and its interactive effect on satellite species was more pronounced (Holmes, 1987).

On the other hand, the ability to absorb nutrients is a function of the surface area and the requirement for nutrients is a function of worm biomass. These factors are involved in the changes of body shape of tapeworms or acanthocephalans, which go with intraspecific (Read, 1951) or interspecific competition (Holmes, 1961). We have now studied the infracommunity structure of gastrointestinal helminths in a population of Alpine marmot, in which there is competition of Ctenotaenia marmotae (a large Cestoda Anoplocephalidae) with other helminth species and interference with the body size and number of tapeworms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Marmots (20 specimens) were collected during autumn (September and October) 1988 from four alpine valleys (San Martino Valley, Fassa Valley, Daone Valley, Pejo Valley) in Trentino-Alto Adige (Eastern Alps, Italy). Helminths were collected and processed by conventional techniques. All worms were identified and counted. Cestodes were measured, fixed in 70 % alcohol and also stained in aceto-alum carmine solution.

The structure of infracommunity helminthics and their distribution in the niche space was studied on the basis of Hanski's core and satellite species hypothesis (Hanski, 1982). Species richness is the number of helminth species per marmot (Southwood, 1978).

RESULTS

All the marmots had gastrointestinal nematodes. Six helminth species (1 Cestoda and 5 Nematoda) were found. Each marmot was infected with 1 to 3 helmirnth species. 55 % of hosts harboured 2 species, 22 % 3 species and 22 % 1 species. Prevalence and abundance values are listed in Table 1.

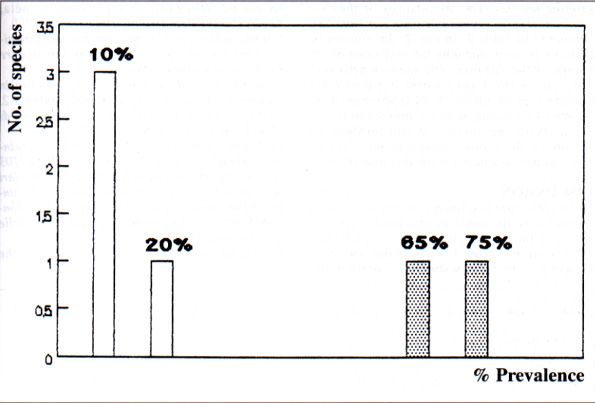

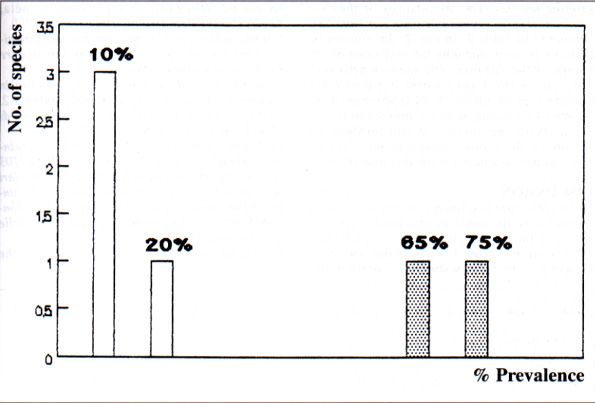

34 % of the hosts examined were infected by fewer than 20 worms and 10 % with more than 850 worms. The average number of worms per host was 230. Frequency distribution of prevalences of helminth species in the host population was bimodal (Fig. 1).

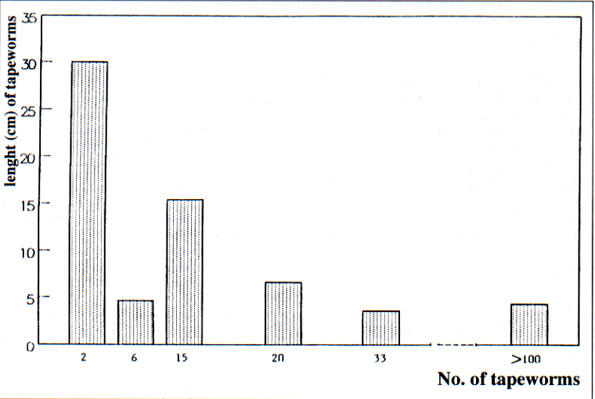

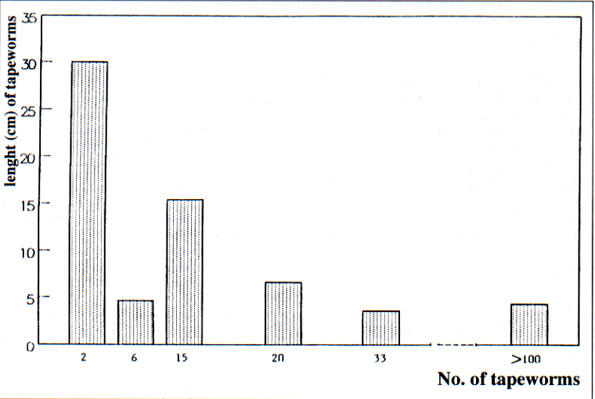

The most frequent species were also the most abundant. Species with a prevalence >65 % are regarded as core species. Those with a prevalence <20 % are regarded as satellite species. No secondary species (>20 % <65 %) were found. Only two species which occurred frequently and in large numbers were considered to be core species (Ctenotaenia marmotae, Cestoda, Anoplocephalidae, and Citellina alpina, Nematoda, Oxyuridae). Four species which occurred infrequently and in low numbers were regarded as satellite species (Teladorsagia circumcincta, Ascaris laevis, Capillaria sp, Trichuris sp). The infracommunity in each marmot had more core species (>55 %) than satellite species. The abundances of the two core species recovered from each host are compared in Table 2. In Fig. 2, the number of cestodes is compared with the variations of the length of the strobila. The mean length was 4.32 cm in the larger worm burdens (103 cestodes), in which 59.2 % of tapeworms were 3 cm to 4.5 cm long with the maximum length 7 cm. With the smaller worm burdens (2 cestodes), the tapeworm length was 30 cm. The shortest specimens were also immature.

DISCUSSION

Helminth species found in marmot from Trentino are the same as previously reported in other parasitological surveys (Jettmar, 1951, Horning, 1969, 1971, Sabatier, 1989).

However, our results showed a predictable infracommunity containing 2 readily discernible units, one composed of common, abundant and characteristic core species, the other one of infrequent and unpredictably occurring satellite species. The core species Ct. marmotae or/and Citellina alpina provide the basic structure of the helminth infracommunity, while the satellite species are a random element of the community.

The satellite species Teladorsagia circumcincta is usually reported for many domestic and wild ruminants.

The occurrence in the marmot should be regarded as a relatively important occasional phenomenon, although they frequently share pastures with ruminants, with high chance of becoming infected. T. circumcincta is dominant either in abundance or prevalence in the helminthic infracommunity of ruminants such as chamois or sheep.

The low values for richness show a poor species infracommunity (mean richness = 0.3). This result agrees with Zhaltsanova's survey (1980) of Marmota bobac, which were infected by 5 species, unlike of other Sciurids species (Sciurus vulgaris, Tamias sibiricus, Citellus undulatus), which were infected by 10, 9 or 23 species. As Kennedy suggested (1986), the main factor in the production of the helminth community is the host's food habits. Broad diets lead to diverse helminth communities while selective feeding leads to large infrapopulations of fewer parasites. Using the mean number of worms as a measure of habitat use by the parasite (Stock and Holmes, 1988), our results (table 2) suggest a negative interaction between Ctenotaenia marmotae (Cestoda) and Citellina alpina (Nematoda). The presence of Ct. Marmotae might also affect the presence and the numbers of the other helminth species. However, more observations are needed to confirm this. Moreover, the presence of large numbers of tapeworms affects changes of body size of specimens (crowding effect). In fact, the length of Ct. marmotae specimens appeared to be inversely related to the number of worms.

COMUNITÀ ELMINTICA NELLA MARMOTTA ALPINA

Manfredi M.T. *, Zanin E. **, Rizzoli A.P. *

*Istituto Patologia Generale, Facoltà di Medicina Veterinaria, Università degli studi di Milano;

**Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie, sezione di Trento.

Introduzione

Nonostante siano state condotte numerose indagini parassitologiche su Marmota marmota, limitate sono le conoscenze sulla struttura gerarchica della infracomunit√† elmintica gastrointestinale di questo roditore Sciurida. La revisione pi√Ļ completa comprendente ecto- ed endo-parassiti √© quella di Sabatier (1989).Diversi fattori possono intervenire nel regolare l'abbondanza e la diversit√† elmintica, e ira questi il comportamento, la "vagility", la dieta e l’habitat dell'ospite sono fondamentali. La diversit√† dell'infracomunit√† pu√≤ essere anche determinata dalla interazione potenziale elminta-elminta. E stato infatti osservato che i cestodi e gli acantocefali sono spesso dominanti nelle comunit√† elmintiche enteriche, per la capacit√† di assorbire sostanze nutritive attraverso la propria superficie corporea (Smith, 1969). A questo proposito, Dioecocestus asper (cestode di grandi dimensioni) √® risultato dominante nella infracomunit√† dello Svasso dal collo rosso (Podiceps grisegena) e il suo effetto interattivo era pi√Ļ pronunciato nei confronti delle specie satelliti (Holmes, 1987).

D'altra parte, la capacit√† di assorbire sostanze nutritive √® in funzione dell'area di superficie corporea e la necessit√† delle stesse √® dipendente dalla biomassa del parassita. Questi fattori sono responsabili della modificazione delle dimensioni corporee di cestodi o acantocefali in situazioni di competizione interspecifica (Holmes, 1961) o infraspecifica (Read, 1951). √Č stata studiata la struttura dell'infracomunit√† degli elminti gastrointestinali in una popolazione di marmotte alpine, in cui Ctenotaenia marmotae (cestode Anoplocephalidae di grandi dimensioni) √® risultata in competizione con altre specie elmintiche. Inoltre, √® stato osservata l'interdipendenza tra il numero dei cestodi e le variazioni di dimensioni corporee degli stessi.

Materiali e metodi

Le marmotte (20 esemplari) sono state raccolte nel periodo da settembre a ottobre 1988 in quattro vallate alpine (Valle di San Martino, Val di Fassa, Val di Daone, Val di Pejo) del Trentino Alto Adige (Alpi Orientali). I parassiti sono stati raccolti e analizzati secondo le tecniche usuali.Tutti gli elminti sono stati identificati e contati. I cestodi sono stati misurati, fissati in alcool al 70 % e colorati al carminio aceto-alluminico.

La struttura della infracomunità elmintica e la loro distribuzione nella nicchia è stata studiata sulle basi dell'ipotesi di Hanski (1982) delle specie core e specie satelliti. La richness di specie é il numero di specie elmintiche per ciascuna marmotta (Southwood, 1978).

Risultati

Tutte le marmotte esaminate sono risultate positive per nematodi gastrointestinali. Sono state identificate 6 specie elmintiche (1 Cestoda e 5 Nematoda). Ciascuna marmotta era infestata da 1 a 3 specie elmintiche. Il 55 % degli ospiti era infestato da 2 specie, 11 22 % da 3 e 11 22 % da 1 specie elmintica. Nella tabella 1 sono elencati i valori di abbondanza e di prevalenza relativi alle specie reperite. Il 34 % degli ospiti √® risultato infestato da poco pi√Ļ di 20 parassiti e il 10 % presentava pi√Ļ di 850 parassiti. Il numero medio di parassiti per ospite era di 230. La distribuzione di frequenza delle prevalenze delle specie elmintiche nella popolazione ospite era bimodale (fig. 1). Le specie di pi√Ļ frequente riscontro erano anche le pi√Ļ abbondanti.Le specie con valori di prevalenza >65 % sono state considerate specie core mentre quelle con prevalenza <20 % specie satelliti. Non sono state invece reperite specie secondarie (>20 % <65 % ). Solamente 2 specie che compaiono frequentemente e in grande numero sono risultate specie core (Ctenotaenia marmotae, Cestoda, Anoplocephalidae, e Citellina alpina, Nematoda, Oxyuridae).Quattro specie che compaiono infrequentemente e in numero limitato sono risultate specie satelliti (Teladorsagia circumcincta, Ascaris laevis, Capillaria sp, Trichuris sp).

L'infracomunità in ciascuna marmotta era costituita da una maggior quantità di specie core (>55 % ) che specie satelliti.

Le abbondanze delle 2 specie core reperite in ciascun ospite sono comparate nella tabella 2. Nella fig 2 è invece confrontato il numero di cestodi e la lunghezza della strobila.

La lunghezza media √® risultata di 4.32 cm quando l'abbondanza delle tenie era pi√Ļ elevata (103 cestodi). In questo caso il 59.2 % degli esemplari misurava da 3 a 4.5 cm di lunghezza e la lunghezza massima era di 7 cm. A valori di abbondanza inferiori (2 cestodi), la lunghezza delle strobile era di 30 cm

Gli esemplari pi√Ļ corti sono risultati anche immaturi.

Discussione

Le specie elmintiche identificate nelle marmotte provenienti dal Trentino sono state precedentemente descritte nel corso di altre indagini parassitologiche (Jettmar,1951, Horning, 1969, 1971, Sabatier, 1989). I risultati da noi ottenuti indicano che l'infracomunità di questo roditore ha una struttura "prevedibile" contenente 2 unità distinte, una costituita da specie dominanti o core, comuni e abbondanti nello stesso tempo, l'altra da specie satelliti che compaiono invece infrequentemente e senza prevedibilità.Le specie core Ctenotaenia marmotae e/o Citellina alpina costituiscono la struttura base dell'infracomunità elmintica, mentre le specie satelliti sono un elemento casuale della comunità stessa.Tra queste, Teladorsagia circumcincta è abitualmente segnalata in molte specie di ruminanti domestici e selvatici. La comparsa nelle marmotta dovrebbe essere considerata come un fenomeno occasionale relativamente importante, benchè esse frequentemente condividono il pascolo con specie ruminanti, con il rischio elevato di infestazione. Peraltro, T. circumcincta è specie dominante sia come abbondanza e prevalenza nella infracomunità di ruminanti quali il camoscio o la pecora.

I bassi valori di richness indicano un infracomunità costituita da poche specie (richness media=0.3). Ciò è conforme anche ai risultati di Zhaltsanova (1980), in cui in esemplari di Marmota bobac erano state identificate solo 5 specie elmintiche, mentre in altre specie di Sciuridi (Sciurus vulgaris, Tamias sibiricus, Citellus undulatus) furono identificate rispettivamente ben 10, 9 e 23 specie.In base a quanto affermato da Kennedy (1986), il principale fattore nella formazione della comunità elmintica è il comportamento alimentare dell'ospite. Diete alimentari ampie e variate portano a una comunità elmintica diversificata, mentre abitudini alimentari selettive implicano una vasta infrapopolazione ma costituita da poche specie parassite. Infine, utilizzando il numero medio di parassiti come misura dell'uso dell'habitat (Stock e Holmes, 1988), i nostri risultati (tab. 2) indicano una interazione negativa tra Ctenotaenia marmotae (Cestoda) e Citellina alpina (Nematoda). La presenza di C. marmotae potrebbe influire anche sulla presenza e sul numero di altre specie elmintiche. Tuttavia, ulteriori osservazioni sono necessarie per confermare questo. Inoltre, la presenza di un elevato numero di cestodi in alcuni soggetti sembra in grado di indurre modificazioni delle dimensioni corporee di parassiti stessi (crowding effect).In particolare, la lunghezza degli esemplari di Ct. marmotae appare inversamente correlata alla loro abbondanza.

Table 1: Composition of gastrointestinal parasite communities of the Alpine marmot.

|   |

P  |

A  |

D |

|

Teladorsagia circumcincta  |

20%  |

0.3  |

0.15% |

|

Ascaris laevis  |

10%  |

2.1  |

0.95% |

|

Capillaria sp  |

10%  |

0.1  |

0.05% |

|

Ctenotaenia marmotae  |

75%  |

20  |

8.97% |

|

Citellina alpina  |

65%  |

211.2  |

89.57% |

|

Trichuris sp  |

10%  |

0.5  |

0.25% |

|

P (prevalence) = frequency of parasite occurrencc |

|

A (abundance) = mean number of parasites pcr host |

|

D (density) = % of one parasite specics in total parasite specics |

ritorno/back

Fig. 1 : Frequency distribution of prevalence of intestinal helminths in marmots.

ritorno/back

Fig. 2 : comparison of the number and the length of cestodes recovered in marmots.

ritorno/back

Table 2: Comparison of numbers oftwo core species recovered from each host.

ritorno/back

|

Host number  |

1  |

2  |

3  |

4  |

5  |

6  |

7  |

8  |

9  |

10  |

11  |

12  |

13  |

14  |

15  |

16  |

17  |

18  |

19  |

20 |

|   |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ctenotaenia marmotae  |

103  |

0  |

0  |

2  |

15  |

1  |

33  |

20  |

6  |

8  |

2  |

38  |

0  |

0  |

27  |

13  |

0  |

21  |

9  |

1 |

|

Citellina alpina  |

0  |

7  |

868  |

0  |

469  |

452  |

0  |

2  |

0  |

410  |

0  |

2  |

10  |

801  |

0  |

421  |

403  |

3  |

0  |

380 |

ritorno/back

REFERENCES

BEVERIDGE I. 1978. A taxonomic revision of the genera Cittotaenia Riehm, 1881, Ctenotaenia, Raillet, 1893, Nosgovoyia, Spasskii 1951 and Pseudocittotaenia Tenora, 1976. (Cestoda: Anoplocephalidae). Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. Série A, Zoologie. Tome 107.

BUSH A.O, HOLMES J.C. 1986. Intestinal helminth of lesser scaup ducks: pattems of association. Can. J. Zool., 64: 132141

HANSKI I. 1982. Dynamics of regional distribution: The ocre and satellite species hypothesis. Oikos, 38: 210-221.

HOLMES J.C. 1961. Effects of concurrent infections on Hymenolepis diminuta (Cestoda) and Moliniformis dubius (Acanthocephala). I. General effects and comparison with crowding. Joumal of Parasitology, 47: 209-216

HORNING B. 1969. Parasitologische untersuchungen an Alpenmurmeltieren (Marmota marmota) der Schweiz. Zb. naturh. Mus. Bern, 137-200

HORNING B., TENDRA F. 1971. The present state of knowledge of cestodes of marmots (genus Marmota). Ver. csl. Spol., zool., 35 (2): 103-106

HUGOT J.P. 1980. Sur le genre Citellina Prendel, 1928 (Oxyuridae, Nematoda). Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp., 55 (1): 97-109

JETTMAR H.M. von, ANSCHAU M. 1951. Beobachtungen an Parasiten steirischer Murmeltiere. Zeitschrift fur Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie, 3: 411-428

PERSSON L. 1985. Asymmetrical competition: Are larger animals competitively superior? American naturalist, 126: 261-266

READ C. P. 1951. The "crowding effect" in tapeworm infections. Journal of Parasitology, 37: 174-178.

SABATIER B.,1989. Les parasites de la marmotte alpine: étude dans les Alpes françaises et synthèse bibliographique. Thèse. Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Lyon.

SMYTH J.D. 1969. The physiology of Cestodes. Oliver and Boyd LTD. Edimburgh.

SOUTHWOOD T. E. 1978. Ecological methods. Chapman and Hall Editors, London.

STOCK M.T., HOLMES J.C. 1987. Dioecocestus asper (Cestoda: Dioecocestidae): an interference competitor in an enteric helminth community. J. Parasit., 73 (6) L: l16-123.

STOCK M.T., HOLMES J.C. 1988. Functional relationships and microhabitat distributions of enteric helminths of grebes (Podicipedidae): the evidence for interactive communities. J. Parasit., 74 (2): 214-227.

ZHALTSANOVA D.S.S., MATUROVA R. T., BRYKOVA L. N. 1980. The helminth fauna of rodents from the family Sciuridae in the South West of Zabaikalie. Fauna i resursy pozvonochnykh basseina ozera Baikal, 41-46

ritorno/back

Tornare index / back contents