Bassano B., Durio P., Gallo Orsi U., Macchi E

eds., 1992. Proceedings of the 1st Int. Symp. on

Alpine Marmot and genera Marmota, Torino.

Edition électronique, Ramousse R., International Marmot Network, Lyon 2002

RESTRICTED MARMOT POPULATIONS IN THE JURA: A POPULATION VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS

Neet C. R.

Centre de conservation de la faune, d'écologie et d'hydrobiologie appliquées 1, chemin du Marquisat, CH - 1025 St-Sulpice, Switzerland

Abstract - During the last hundred years and especially in the last twenty years, about 150 Alpine Marmots (Marmota marmota) have been reintroduced in several sites of the Swiss Jura Mountains. At present time, the populations are all restricted, both in space and in population size, and recent field studies indicate that the populations are remaining rather stable.

Such reintroduced and restricted populations are exposed to considerable extinction risks. Population Vulnerability Analysis (PVA) is an integrated approach designed to deal with such cases where reduced viability is expected on the grounds of habitat quality, inbreeding, regional catastrophes and demographic processes that occur in small populations.

We present a simple PVA for the Marmot populations of the Jura and assess extinction risks on the basis of population data collected by Humbert-Droz & Thossy (1990) and the Centre de conservation de la faune, St-Sulpice, Switzerland. The problems of conservation and management are discussed in connection with the high risk of extinction of the Jura metapopulations.

INTRODUCTION

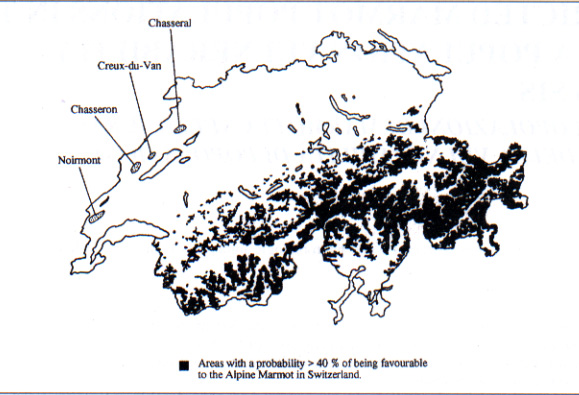

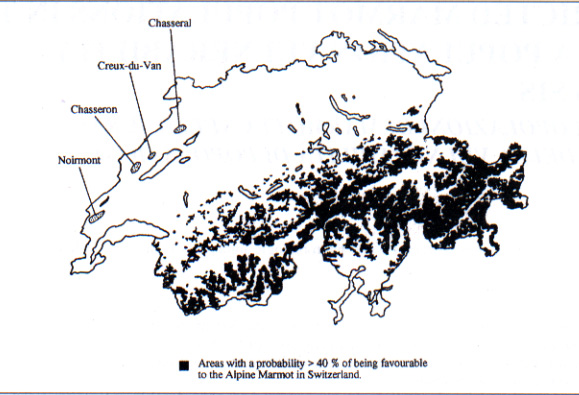

During the last hundred years and especially during the last twenty years, some 150 Alpine Marmots (Marmota marmota) have been reintroduced in several sites of the Swiss Jura Mountains, after having been absent from these mountains since the last glaciations (Schnorf, 1963). Marmots were reintroduced in 4 principal areas (Fig. 1) that are separated by considerable barriers that seriously prevent natural exchanges between the areas. At present time, in each of these areas, a metapopulation structure is found, composed of about 3 to a dozen of colonies. In each colony, minimal numbers of observed animals varied between 1 and 15 in 1988 and 1989 (Humbert-Droz & Thossy, 1990). These metapopulations are all restricted, both in distributional range and in population size, and are therefore exposed to considerable extinction risks. Population Vulnerability Analysis (PVA) is an integrated approach designed to deal with such cases where a reduced viability may be expected on the grounds of habitat insularity, inbreeding, regional catastrophes and demographic processes that occur in small populations, e.g Gilpin (198?); Burgman & Neet (1989). In order to assess the viability of these Marmot populations of the Jura and to define a management programme, we have conducted a simple population vulnerability analysis that successively examines different aspects of extinction risk analysis, i.e. habitat quality, extinction risks in relation with genetic and demographic factors, and catastrophic effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The 4 metapopulations of the Swiss Jura Mountains include 25 colonies. In this study, we have limited the work to the canton de Vaud, which includes two metapopulations (Table 1). We define a metapopulation as a group of colonies between which exchanges of migratory individuals occurs, according to our observations in the field and to the weak geographical barriers that separate the colonies. The minimal numbers of individuals observed in recent years in these metapopulations are given in Table 2. The population viability assessments were made on the basis of these population data, which were collected by Humbert-Droz & Thossy (1990) and the Centre de conservation de la faune, St-Sulpice, Switzerland. The population vulnerability analysis methods are described in the results section.

RESULTS

Population data

The reintroduction process in the Jura has a complex history, and several attempts have failed. Many reintroductions were done with very few individuals (<10). However, in the Chasseron metapopulation it has been quite successful (Tables 1 & 2). Unfortunately, the exact origin of this metapopulation is not known. The Norman metapopulation is much more recent and, interestingly, most localities where the Marmots were introduced are not occupied anymore. All actual colony sites except one have been founded by the reintroduced Marmots themselves, and all are quite recent, i.e. not older than 16 years (Table 1). Available population data are in the form of minimal numbers of observed individuals. Such data only give a very approximate indication of actual population sizes. However, the data given in Tables 1 & 2 show that there is some degree of persistence of these small colonies.

Habitat quality analysis

In order to be able to predict the potential distributional range of Swiss mammals, Hausser & Bourquin (1988) have developed a computer program that uses observed locations of a species and many variables of several data bases such as the vegetation map of Switzerland and climatic databases to calculate and draw potential areas of distribution. The potential areas of given species are statistically estimated as areas having a degree of similarity with the areas where the species have actually been observed. In fig. 1 the areas having a probability >40% of being favourable for the Alpine Marmot are shown, as well as the actual sites where marmots are found in the Swiss Jura mountains. This map clearly shows that the Jura habitats are not very favourable for the Marmot according to this potential range estimation. If one examines the maps produced by Hausser & Bourquin (1988), one can actually see that the few areas mapped as potential marmot sites in the Jura have a probability of being favourable that lies in the 20-40% range. This low habitat quality of the Jura can be explained by the ecological needs of Alpine Marmots, which are known to be mainly distributed at altitudes over 1400 m, beyond the limit of the forest (Muller, 1988), whereas in the Jura they are in the 1000-1450 m range, usually below the upper limit of the forest (Humbert-Droz & Thossy, 1990).

Another important aspect of the Jura habitat is its insularity, the habitats being separated by forests and valleys. This factor is important since the metapopulations present in the Jura Mountains are completely separated and thus isolated from a demographic and genetic point of view. The habitat quality is also diminished, at least in metapopulations studied here, by the fact that several colonies live in farmed areas, which are submitted to pasture, nitrification and disturbance by dogs, or by predators such as foxes (which are abundant in the area).

Extinction risks in relation with genetic factor.

Many population viability analyses are based on the principle that in small populations, inbreeding can greatly reduce the average individual fitness, and loss of genetic variability from random genetic drift can diminish future adaptability to a changing environment (Lande, 1988).

Although it has been subject to some criticism e.g. Simberloff, 1988), we will here consider the 50/500 rule as a reference for the genetic part of the PVA. This rule states that a minimum effective population size of 50 would be required to stem inbreeding depression, while an effective population size of 500 would prevent long term erosion of genetic variability by drift. According to Mace & Lande (1991), we may roughly admit that an effective population size of 50 corresponds to a population of 100 to 250 individuals.

With the minimal numbers of individuals observed in the metapopulations of Marmots (Table 2), we are probably under this level. Does this mean that the marmots will rapidly become extinct? Not necessarily. As underlined by Simberloff (1988), neither inbreeding nor low genetic variability will automatically lead to inbreeding depression. It will actually very much depend on the presence of deleterious alleles and on their persistence in the population. Moreover, the actual metapopulation structure may, at least theoretically, lead to some countereffects to the loss of genetic variability (McCauley, 1991). A solution to the risk of inbreeding depression is to promote panmixia by moving as few as one or two individuals at random into each colony per generation (Lande & Barrowclough, 1987), or to add new individuals imported from highly populated areas of the Alps.

This second point is not without danger. As mentioned by Simberloff (1988), who reviewed several examples of outbreeding depression in reintroduced wild populations, although outbreeding depression due to the introduction of alien gene sets is likely to be temporary, it can be severe enough to increase chances of extinction.

A simple security rule would be to add individuals taken from the same populations that have served to establish the first colonies of the Swiss Jura.

Extinction risks in relation with demographic factors

Lande (1987, 1988) has shown that in very small populations, the major problem is a demographic one. The Allee effect for example, is a decline due to the fact that the population is below a threshold density at which sufficient contacts between individuals occur to ensure a viable level of reproduction. Lande (1987) has also clearly shown that when the relative amount of favourable habitat relative to the total area of a site is low, the populations are exposed to severe extinction risks for demographic reasons. In the Jura, given the relatively low amounts of favourable habitats and their insularity, this risk certainly exists. The problem of extinction risks due to demographic factors has also been modelled in a very general way by Goodman (1987). His model calculates the persistence time of a population using two parameters: the growth rate of the population and the variance of this growth rate. This model has been adapted to mammals in order to permit rapid and rough estimates of viability on the simple basis of body mass (Belovsky, 1987).

Belovsky's approach actually relies on the allometric relationship that permits to estimate the maximal growth rate from body mass. Belovsky estimated the variance of the growth rate empirically, using field data, and found it to range between 1.43 r (Low Variance) and 7.32 r (High Variance).

The solution of the model is in the form of a correlation between body weight and the population size necessary to ensure a 95% probability for the population to persist 100 or 1000 years (Belovsky, 1987). Using a mean body mass of 4 kg (Krapp, 1978), we calculated the population sizes needed to ensure viability according to this model (Table 3).

The results given in Table 3 are rough and do not take all necessary parameters into account. However, the viable population sizes are so large that even if they are overestimated to some extent, there is little doubt that the Jura populations are seriously threatened of extinction.

Extinction risks in relation with catastrophes

A typical catastrophe for Marmot metapopulations would be an epidemic disease.

Some possible diseases are mentioned by Muller-Using & Muller-Using (1972). The risks of extinction in the presence of catastrophes have been examined by several authors (see Burgman & Neet, 1989).

The essential point with respect to Marmots is that the best protection against local catastrophes is to have a metapopulation structure with weak migration levels between the colonies. Given the lack of data concerning the levels of migration, it is not possible to assess any degree of risk for this aspect of the PVA.

DISCUSSION

PVA is still a rather theoretical methodology. Practical assessment tools have however been developed and are useful to construct rough estimates of the risks of extinction of a species like the Alpine Marmot.

In the case of the reintroduced populations of the Jura, the risks of extinction are obviously high, for at least four major reasons: 1) the habitat is suboptimal, 2) the habitat is limited and highly fragmented, 3) the effective population sizes are below the minimal sizes to escape a serious probability of inbreeding depression, and 4) the population sizes are very low with respect to demographic factors. Given these constraints, one may either decide to leave the Marmots to their destiny, or to start a conservation programme. If left without management, these metapopulations would provide an interesting natural experiment, especially in the case of the Chasseron metapopulation that bas lasted for several decenies. However, given the results of this viability assessment, a management plan is certainly a necessary step to prevent an almost certain extinction.

This plan should act on the four factors identified above, i.e.: 1) protect the occupied habitats and minimize habitat alteration by man-induced nuisances, 2) favour the metapopulation organization by maintaining a sufficient amount of available habitats, at reasonable distances from each other, 3) displace individuals or introduce a new individual per generation in order to maintain genetic variability, 4) undertake colony monitoring in order to detect local extinctions due to demographic deficiencies and move individuals when necessary. Such a management plan will have to be supported financially and will have some local consequences on land-use. Therefore the choice between the two alternatives for the future of the Marmot in the Jura will have to be made by wildlife authorities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Corinne Humbert-Droz, Marika-Luce Thossy and Prof. Claude Mermod of the University of Neuchatel for having undertaken a complete survey of the Marmots in the Jura in 1988/1989. We would also like to thank Michel Conti, Patrick Deleury and Bernard Reymond for their field observations.

ESIGUE POPOLAZIONI DI MARMOTTA NELLO JURA: ANALISI DELLA VULNERABILITÀ DI POPOLAZIONE

Neet C. R.

Centre de conservation de la faune, d'écologie et d'hydrobiologie appliquées 1, chemin du Marquisat, CH - 1025 St-Sulpice, Switzerland

Introduzione

Durante gli ultimi cento anni, ed in particolare negli ultimi 20, circa 150 marmotte alpine (Marmota marmota) sono state reintrodotte in numerose località delle montagne dello Gura svizzero, hanno visto la scomparsa di detta specie durante l'ultima glaciazione (Schnorf 1963). Le marmotte sono state reintrodotte in quattro aree principali (Fig. 1), separate da notevoli barriere naturali, che rendono fortemente improbabili scambi tra le diverse popolazioni. Al momento, in ciascuna di queste aree esiste una struttura da metapopolazione composta da 3-12 colonie. In ogni colonia il numero minimo di animali osservati varia da 1 a 15 individui (anni 1988 - 1989 - Humbert-Droz e Thossy, 1990).Tutte queste metapopolazioni hanno dimensioni ridotte ed una distribuzione geografica limitata e sono quindi esposte a gravi rischi di estinzione. L'Analisi di Vulnerabilità di Popolazione (PVA) é un approccio integrato studiato per analizzare i casi in cui é attesa una ridotta capacità di sopravvivenza della popolazione, sulla base di insularità dell'habitat, consanguineità, catastrofi regionali e processi demografici, che avvengono in popolazioni piccole (vedi ad es. Gilpin, 1987; Burgam e Neet, 1989).

Al fine di valutare la vitalità delle popolazioni di Marmotta dello Gura e di definire un programma di gestione, si é condotta una semplice analisi di vulnerabilità che esamina, in successione, i differenti aspetti dell'analisi dei rischi di estinzione, ovvero la qualità dell'habitat, i rischi di estinzione in relazione a fattori genetici e demografici ed gli effetti delle catastrofi naturali.

Materiali e metodi

Le quattro metapopolazioni delle montagne dello Gura svizzero comprendono 25 colonie. in questa analisi abbiamo limitato la studio al cantone di Vaud, che comprende due metapopolazioni (Tab. 1). Viene definita come metapopolazione un insieme di colonie in cui avvengono scambi di soggetti migratori dimostrabili in base alle nostre osservazioni sui campo o per l'assenza di barriere insormontabili.

Il numero minimo di individui osservati negli ultimi anni é indicato in Tabella 2. La stima della vitalità della popolazione é stata effettuata sulla base dei dati raccolti da Humbert-Droz e Thossy (1990) e dal Centre de Conservation de la Faune, St-Sulpice, Svizzera.

Il metodo di analisi di vulnerabilità di popolazione viene descritto nella sezione "Risultati ".

Risultati

Dati di popolazione

La storia della reintroduzione della Marmotta √© complessa e molli tentativi sono falliti.Molte operazioni sono state effettuate con pochissimi animali (<10). Ci√≤ nonostante, nel caso della metapopolazione di Chasseron, il successo √© stato raggiunto (Tabelle 1 e 2). Sfortunatamente non √© nota l'esatta origine di questa metapopolazione. La metapopolazione di Noirmont √© invece pi√Ļ recente e merita ricordare che oggi molte delle localit√† dove le marmotte sono state rilasciate non sono pi√Ļ occupate. Tutti gli attuali siti, eccettuato uno, sono stati scelti dalle marmotte stesse e tutte sono piuttosto recenti, sono cio√® occupati da non pi√Ļ di 16 anni (Tab. 1).I dati demografici sono rappresentati dal numero minimo di individui osservati direttamente. Tali dati forniscono solo un'indicazione generica delle reali dimensioni della popolazione. Comunque essi dimostrano (Tabelle 1 e 2) che un certo grado di stabilit√† in queste piccole colonie esiste.

Analisi della qualità dell'habitat

Per analizzare e disegnare le mappe della distribuzione potenziale dei mammiferi svizzeri, Hausser e Bourquin (1988) hanno sviluppato un programma computerizzato che utilizza: l'analisi dei dati relativi ai siti effettivamente occupati dalla specie, accanto a quella di altre variabili, contenute in banche dati informatizzate (Carta della vegetazione della Svizzera e Dati climatici). Le zone vocate per una determinata specie vengono individuate statisticamente in base alla loro similitudine con i siti effettivamente occupati. In Fig. 1 sono indicate le aree che hanno pi√Ļ del 40% di probabilit√† di essere favorevoli all'insediamento della Marmotta alpina, in altre parole i siti in cui le marmotte sono effettivamente presenti nello Gura svizzero. Questa carta indica chiaramente che l'habitat dello Gura non √© molto favorevole per la Marmotta. Esaminando attentamente le carte prodotte da Hausser e Bourquin (1988) si pu√≤ vedere che le poche zone indicate come potenzialmente idonee all'insediamento della Marmotta nello Gura hanno una probabilit√† di essere realmente favorevoli del 20-40 %.

Questa limitata vocazionalit√† dello Gura pu√≤ essere spiegata in base a quelle che sono le necessit√† ecologiche della Marmotta alpina. Essa √© per la pi√Ļ distribuita ad altitudini superiori a 1400 m, al di sopra del limite della foresta (M√ľller 1988), mentre nello Gura vive tra i 1000 e i 1450 m, generalmente al di sotto del limite della vegetazione arborea (Humbert-Droz e Thossy, 1990).

Un altro aspetto importante dell'habitat della Gura é la sua insularità, in quanto questi sono separati da foreste e valli. Questo fattore é importante in quanto le metapopolazioni presenti nelle montagne dello Gura sono completamente separate e quindi isolate da un punto di vista demografico e genetico. La vocazionalità del territorio é anche limitata, per la meno nelle metapopolazioni studiate, dal fatto che molte colonie vivono in aree sfruttate per l'allevamento del bestiame e dunque sottoposte a pascoliane, nitrificazione e disturbo da pane di cani, pastore o randagi. Anche predatori quali la Volpe sono abbondanti in zona.

Rischi di estinzione in relazione a fattori genetici.

Molte analisi di vitalità di popolazioni si basano sui principio che nelle popolazioni piccolo la consanguineità può ridurre di molto la fitness individuale media e che la perdita della variabilità genetica, dovuta alla deriva genetica casuale, può diminuire l'adattabilità della specie ad un ambiente in via di modificazione (Lande, 1988). Anche se ciò é stato criticato (ad es. Simberloff 1988), useremo qui la regola del 50/500 come riferimento per la parte genetica del PVA. Questa regola stabilisce che il numero minimo di individui attivi in una popolazione sia di almeno 50 soggetti per scongiurare una depressione da consanguineità mentre una popolazione di 500 individui attivi dovrebbe evitare l'erosione a lungo tempo della variabilità genetica, dovuta a deriva. Secondo Mace e Lande (1991) possiamo grossolanamente considerare che una popolazione di 50 individui attivi corrisponda a una di 100-250 individui totali. A giudicare dal numero minimo di individui osservati nelle metapopolazioni di Marmotte (Tab. 2), siamo probabilmente al di sotto di tale livello.

Questo significa che le marmotte si estingueranno rapidamente? Non necessariamente. Come sottolineato da Simberloff (1988), né la consanguineità né una scarsa variabilità generica portano ad una depressione da consanguineità. In realtà ciò dipende in gran pane dalla presenza di alleli deleteri e dalla loro persistenza nella popolazione. Inoltre la struttura della metapopolazione può, almeno teoricamente, controbilanciare la perdita della variabilità genetica (McCauley, 1991).

Una soluzione al rischio di depressione da consanguineità é quella di promuovere la panmissia, spostando anche solo uno o due animali a caso in ciascuna colonia ad ogni generazione (Lande e Barrowclough, J987) o aggiungendo nuovi individui prelevati da zone densamente popolate delle Alpi.

Questo secondo sistema presenta dei rischi. Come citato da Simberloff (1988), che ha evidenziato numerosi esempi di depressione genetica da esincrocio, in popolazioni selvatiche reintrodotte, anche se la depressione da esincrocio dovuta all'introduzione di geni alieni sembra essere temporanea, questa può essere abbastanza grave da aumentare le probabilità di estinzione.Una semplice regola di sicurezza sarebbe quella di aggiungere solo individui presi dalla stessa popolazione che é servita per la prima reintroduzione nello Gura svizzero.

Rischi di estinzione in relazione a fattori demografici.

Lande (1987, 1988) ha dimostrato come in popolazioni molto piccole, il problema pi√Ļ grave sia quello demografico.

L'effetto Allee, per esempio, é un fenomeno di declino genetico dovuto al fatto che la popolazione si trovi al di sotto di una soglia limite di densità, oltre la quale avvengono contatti tra gli individui in numero sufficiente da assicurare un livello vitale di riproduzione.

Lande (1987) ha inoltre dimostrato chiaramente che, quando l'estensione dell'habitat favorevole, rispetto all'area totale del sito, é bassa, le popolazioni sono esposte a grave rischio di estinzione per ragioni demografiche. Nello Gura, data la limitatezza dei territori favorevoli e la loro insularità, il rischio certamente esiste.

Il problema dei rischi di estinzione dovuti a fattori demografici é stato modellato in modo generale da Goodman (1987).

Il suo modello calcola il tempo di persistenza di una popolazione in base a due parametri: il tasso di crescita della popolazione e la varianza di questo tasso.Questo modello é stato adattato ai mammiferi al fine di permettere una stima grossolana ma rapida della vitalità di una popolazione sulla semplice base della massa corporea (Belovsky, 1987).

L'approccio di Belovsky si basa sulla relazione allometrica che permette di stimare il lasso di incremento massimo dalla mole corporea. Belovsky ha stimato la varianza del tasso di crescita empiricamente, utilizzando dati raccolti sui campo, e ha trovato che essa variava tra 1.43 r (Varianza bassa) e 7.32 r (Varianza alla). La soluzione del modello é data da una correlazione tra la massa corporea e la dimensione che la popolazione deve avere per raggiungere il 95 % di probabilità di sopravvivere per 100 o 1000 anni (Belovsky, J987).

Considerando per la Marmotta una massa corporea media di 4 Kg (Krapp 1978), abbiamo calcolato le dimensioni necessarie per assicurare la sopravvivenza di una popolazione, secondo questo modello (Tab. 3).

Il risultato fornito in Tabella 3 é puramente indicativo, in quanto non sono state tenute in considerazione tutti i parametri necessari.

Comunque le dimensioni vitali di una popolazione teorica, per quanto sovrastampare, sono talmente grandi da fugare ogni dubbio sui rischio effettivo di estinzione delle popolazioni dello Gura.

Rischi di estinzione in relazione alle catastrofi

Una tipica catastrofe per una metapopolazione di Marmotta potrebbe essere una malattia epidemica. Alcune possibili malattie sono citate da Muller-Using e Muller-Using (1972).

I rischi di estinzione in presenza di catastrofi naturali sono stati esaminati da numerosi Autori (Burgman e Neet, 1989).

Per quel che riguarda la Marmotta, il punto essenziale é che la miglior difesa contro una catastrofe locale é quella di avere una struttura di metapopolazione con bassi livelli di migrazione. Data la mancanza di dati riguardanti il livello di migrazione, non é possibile determinare il grado di rischio per questo aspetto del PVA.

Discussione

Il PVA é ancora una metodologia piuttosto teorica. Strumenti di valutazione pratica sono comunque già stati sviluppati e sono utili per fornire una stima indicativa dei rischi di estinzioni di una specie quale la Marmotta alpina.

Nel caso delle popolazioni reintrodotte nello Jura, i rischi di estinzione sono ovviamente alti, almeno per quattro ragioni principali: 1) L'habitat é subnormale, 2) L'habitat é limitato e frammentato, 3) Le popolazioni attive sono troppo piccole per scongiurare una seria probabilità di depressione da inincrocio e, 4) le popolazioni sono troppo piccole anche rispetto ai fattori demografici. Dati questi limiti si può decidere di lasciare le marmotte al loro destino o di iniziare un programma conservazione. Se lasciate senza gestione queste metapopolazioni possono diventare un interessante esperimento naturale specialmente nel caso della metapopolazione dello Chasseron che esiste già da alcuni decenni. Comunque, dati i risultati di questa valutazione di vitalità, un piano di gestione rappresenta un passo necessario per prevenire una estinzione quasi certa della specie.

Questo piano dovrebbe agire sui quattro fattori sopraindicati: 1) proteggere l'habitat utilizzato e ridurre l'alterazioni ambientali indotte dall'uomo; 2) favorire l'organizzazione delle metapopolazioni mantenendo siti idonei di sufficiente estensione ed a distanza ragionevole tra di loro; 3) spostare gli individui o introdurre un nuovo individuo per ogni generazione al fine di mantenere la variabilità genetica; 4) monitorare le colonie per individuare estinzioni locali imputabili a fattori demografici e spostare degli individui quando necessario.Un tale piano di gestione necessita di un notevole supporto finanziario e avrebbe delle conseguenze locali sull'uso del territorio. Di conseguenza la scelta tra le due alternative per il futuro della Marmotta nello Jura deve essere compiuta dalle autorità competenti in materia.

Ringraziamenti

Siamo molto grati a Corinne Humbert-Droz, Marika-Luce Thossy ed al Prof Claude Mermod dell'Università di Neuchatel per aver intrapreso un'indagine completa sulla Marmotta nello Jura nel periodo 1988/89. Vogliamo anche ringraziare Michel Conti, Patrick Deleury e Bernard Reymond per le osservazioni sul campo.

Figure 1: Map of the distribution of the four metapopulations of Alpine Marmots (Marmota marmota) reintroduced in the Swiss Jura moutains (dotted zones), and map of potential habitats having a probability of > 40 % of being similar to actual locations of the Marmot in Switzerland, according to Hausser & Bourquin (1988).

retour/back

Table1: The two metapopulations of the Canton de Vaud. The first year column indicates when the colony was observed for the first time (ni = natural immigration from introduction sites, in = introduction site still occupied, No = number of individuals observed the first time the colony was discovered)

|

l. Noirmont metapopulation |

|

Colony  |

Locality  |

First year  |

N0 |

|   |

|

1.1  |

Creux du Croue  |

1985 (ni)  |

7 |

|

1.2  |

Combe des Begnines  |

1979 (in)  |

6 |

|

1.3  |

La Valouse  |

1975 (ni)  |

1 |

|

1.4  |

Cabane de l'Ecureuil  |

1979/81 (ni)  |

6 |

|

1 5  |

Les Amburnex  |

1989 (ni)  |

2 |

|

1.6  |

Seche de Gimel  |

1989 (ni)  |

2 |

|

1.7  |

Seche des Amburnex  |

1984/85 (ni)  |

7 |

|

1.8  |

Les Lapies  |

1989 (ni)  |

1 |

|   |

|

2. Chasseron metapopulation * |

|   |

|

2.1  |

Le Sollier  |

19th century  |

|

|

2.2  |

La Merlaz  |

19th century  |

|

|

2.3  |

Les roches éboulées  |

19th century  |

|

|

* 30 individuals were observed in this area in 1945. |

retour/back

Table 2: Minimal numbers of individuals observed in the two metapopulations of the Canton de Vaud. Observation efforts differed between the years

|

Colony  |

numbers of individuals |

|   |

1988  |

1989  |

1990  |

1991 |

|

1. Noirmont |

|

1.1.  |

5  |

1  |

|

|

|

1.2  |

1  |

7  |

|

|

|

1.3  |

12  |

8  |

7  |

|

|

1.4  |

4  |

7  |

13  |

|

|

1.5  |

2  |

4  |

|

|

|

1.6  |

3  |

4  |

|

|

|

1.7  |

6  |

8  |

4  |

|

|

1.8  |

1  |

5  |

|

|

|   |

|

|

|

|

|

Totals: |

22  |

34  |

1  |

45 |

|   |

|

2. Chasseron |

|

2.1  |

15  |

1  |

12  |

|

|

2.2  |

3  |

1  |

5  |

|

|

2.3  |

5  |

3  |

2  |

2 |

|   |

|

|

|

|

|

Totals: |

23  |

5  |

2  |

19 |

retour/back

Table 3: Population sizes (N = standard population size) needed to persist l00 or l000 years with a 95% probability, for a mammal of 4 kg, as predicted by Goodman's extinction model solved by Belovsky (1987)

|   |

95 % persistence |

|

100 years |

1000 years |

|

Environmental variance: |

|

LOW  |

1097  |

10923 |

|

HIGH  |

24842  |

248630 |

retour/back

REFERENCES

BELOVSKY, G.E. 1987. Extinction models and mammalian persistence. In: M.E. Soule (Ed.), Viable populations for conservation, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, pp. 35-57.

BURGMAN, M.A. & NEET, C.R. 1989. Analyse des risques d'extinction des populations naturelles. Acta oecol., Oecul. gener., 10: 233-243.

GILPIN, M.E. 1987. Spatial structurc and population vulnerability. In: M-E. Soule (Ed.), Viable populations for conservation, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridgc, pp. 125-139.

GOODMAN, D. 1987. The demography of chance extinction. In: M.E. Soule (Ed.), Viable populations for conservation. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, pp. Il-34

HAUSSER, J. & BOURQUIN, J.-D. 1988. Répartition de douze espèces de mammifères en Suisse. Atlas des mammifères de Suisse, Société suisse pour l'étude de la faune sauvage, Lausanne.

HUMBEN-DROZ, C. & THOSSY, M.-L. 1990. Localisation et étude de quelques aspects éco-éthologiques des marmottes (Marmota marmota) dans le Jura vaudois, neuchatelois et bernois. Travail de certificat, Institut de Zoologie, Université de Neuchatel.

KRAPP, F. 1978. Marmota marmota (Linnaeus, 1758) - Alpenmurmeltier. In: J. Niethammer & F. Krapp, Handbuch der Saugetiere Europas, Band 1: Nagetiere I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden, pp.153-181.

LANDE, R. 1987. Extinction thresholds in demographic models of territorial populations. Ann. Nat., 130: 624-635.

LANDE, R. 1988. Genetics and demography in biological conservation. Science, 241: 1455-1460.

LANDE, R. & BARROWCLOUGH, G.F. 1987. Effective population size, genetic variation, and their use in population management. In: M.E. Soule (Ed.), Viable populations for conservation. Cambridge Urliv. Press, Cambridge, pp. 87-123.

MACE, G.M. & LANDE, R. 1991. Assessing extinction threats: towards a reevaluation of IUCN threatened species categories. Conserv. Biol., 5: 148-157.

MCCAULEY, D.E. 1991. Genetic consequences of local population extinction and recolonization. Trends Ecol. Evol., 6: 5-8.

M√úLLER, J.P. 1988. Das Murmeltier. Desertina Verlag, Disentis.

M√úLLER-USING, D. & M√úLLER-USING, R. 1972. Das Murmeltier. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Munchen.

SCHNORF, A. 1963. Sur un gisement de marmottes dans le quaternaire du Pied du Jura vaudois. Bull. Soc. vaud. Sc. nat., 68: 291-293.

SIMBERLOFF, D. 1988. The contribution of population and community biology to conservation science. Ann. Rev. Ecul. Syst., 19: 473-511.

Tornare index / back contents